The Friends of Fort Caswell Rifle Range continues to prepare Brunswick County in the Great War: Preserving the 1918 Fort Caswell Rifle Range and the Legacies of the Men and Women Who Served for publishing.

Kathryn Kalmanson, granddaughter of Brunswick County WWI veteran Craven Ledrew Sellers, graciously agreed to share her recent research. Thank you, Kathryn!

“Going through boxes of family papers, I discovered a little WWI gem among my grandfather’s papers. Being curious to identify the writer, I started searching.” The result is shared below. Kathryn was particularly amused at Mr. Wylie calling her grandfather a “splendid boy,” given that Wylie was several years younger.

Brion-S-Ource, France

May 2nd, 1919

Dear Dad:-

This will introduce to you Mechanic Sellers of Co I. 324 Inf who leaves for the States today, having received a discharge.Sellers is a splendid boy and anything you can do to make his stay in Wilmington a pleasant one will be greatly appreciated by me.

Mech. Sellers is from close to Southport.

Sgt. W A Wylie

Insights into the letter of introduction written by Wylie

by Kathryn Kalmanson, granddaughter of Ledrew Sellers

The writer of the letter has been identified as William Abraham Wylie of Wilmington, NC, son of Robert John Knox Wiley, the intended recipient of the letter. Robert, who had come to Wilmington, NC, from Ohio, and his wife Mary lived at 14 Wrightsville Avenue (“at Carolina Place”) where he operated Wilmington Cooperage Company. His two sons, Dwight and William, also lived there and worked in the company. According to a 1908 newspaper article, Robert owned half of the shares in the company which manufactured “staves, headings, barrels, casks, etc.”

William and Ledrew had very different beginnings. William was born April 9, 1893, in Ohio. In 1915, when he was 20 years old, he is listed as foreman at the cooperage, with his father as vice president and his brother Dwight as a cooper. The Wilmington City Directory for 1917 lists William and Dwight as clerks and Robert as Vice President and Treasurer.

Ledrew was born at Supply, NC, on August 7, 1889, the second oldest of ten children born to Elisha and Theodosia Sellers. At that time Elisha was a farmer, and the children all helped with the running of the family farm which was located in the Lockwood’s Folly area of Brunswick County.

1918 was an eventful year for both William and Ledrew. On February first William married Charlotte Fennell and shortly after that the young couple established their own residence at 804 Market Street. A few months later, William received orders to report for military duty.

Ledrew also married shortly before going into service. On May 20, 1918, he and his cousin Lelia Sellers were married at Supply, NC. Exactly one week later Ledrew was inducted, leaving his bride with his family as he went off to war.

It was the war that brought these two young men together. They were inducted on the same day, May 27, 1918, assigned to the same unit, Company I 324th Infantry, and sent to Camp Jackson for training. The unit departed from New York on August 5, 1918, bound for France.

Both men received promotions while serving in France, Private Ledrew becoming Mechanic and Private William becoming a sergeant. It may be that William became Ledrew’s commanding officer and in that context wrote the enthusiastic letter of introduction. Or perhaps they simply became friends while serving together or while waiting in St. Nazaire for departure to the states.

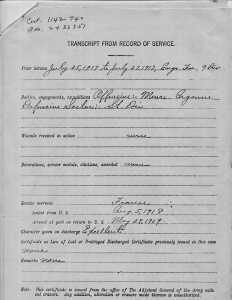

Discharge papers for Mechanic Craven Ledrew Sellers

Ledrew left on May 17, 1919, nearly two weeks after the letter of introduction was written, sailing from St. Nazaire aboard the Antigone, bound for Newport News, VA. Home at last, Ledrew was honorably discharged from service on the first of June 1919. One week later, on June 7, 1919, William sailed from St. Nazaire aboard the Martha Washington to begin the long trip home.

The Wylie House, ca. 1914, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

William and Ledrew’s lives took very different paths after the war, each following in his father’s footsteps. William returned to his father’s home after the war and worked at the cooperage. The 1920 Census shows William and his brother working out of the Wrightsville Avenue address with their father, aged 51, listed as Manager. William was 26 and Dwight 24. In the 1922 Wilmington City Directory, William is listed as clerk and John as manager.

William and Ledrew’s lives took very different paths after the war, each following in his father’s footsteps. William returned to his father’s home after the war and worked at the cooperage. The 1920 Census shows William and his brother working out of the Wrightsville Avenue address with their father, aged 51, listed as Manager. William was 26 and Dwight 24. In the 1922 Wilmington City Directory, William is listed as clerk and John as manager.

It was not a small company for that time. Information from the NC Corporation Commission and the US Engineers reports on the port of Wilmington shows that the cooperage had $15,000 in capital stock. Their wharf was located “south of the foot of Wright Street.” The company also had operations at several other locations, including Charleston, SC.

While William was away at war, tragedy had struck at home: His wife Charlotte died on December 27, 1918, one of the many victims of the great influenza epidemic. In April 1922 he married Sadie McCallum, and they had a daughter, Sarah Elizabeth, born June 19, 1923. She appears to have been their only child. The 1940 Census shows them living at 1403 Rankin Street in Wilmington. William was a lumber salesman and Sadie a “trained nurse.” William’s final occupation, as shown on his death certificate, was “clerk of the federal court.”

The letter of introduction that William wrote for Ledrew may have been a hint for his father to offer Ledrew employment at the cooperage or perhaps it was simply a friendly gesture. In any event Ledrew never presented the letter to Mr. Wylie because it was found still among his papers after his death.

After discharge from the Army, Ledrew returned to his family home where his wife was waiting for him. He continued farming and also worked at a saw mill. Then soon after the birth of their first child, Susan Evelyn, on May 25, 1920, he and Lelia moved to Southport where he became a merchant. They had two more children, Thelma Vashti, born April 11, 1922, and William Rydell, born June 2, 1923. William’s middle name was given to honor a sergeant who served in the war with Ledrew. Did the name William reflect Ledrew’s friendship with William Wylie?

William Wylie died December 27, 1943, at age 50 and was buried in his family plot at Oakdale Cemetery, Wilmington. Ledrew Sellers died June 16, 1960, at age 71 and was buried in the family plot at Northwood Cemetery in Southport. Although William and Ledrew spent the post-war years only about twenty-five miles apart, it appears that they never saw each other again after the day that William penned the note to his father and Ledrew sailed home from France with the note in his pocket.

To read more about Ledrew’s wartime experiences, see his WWI profile here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.